High school students promoted to real researchers

Besides helping to collect samples or spot butterflies for research projects — non-professionals can now conduct actual laboratory work alongside professional researchers. Together with Danish high schools, the University of Copenhagen has shown that "extreme citizen science" doesn’t just strengthen student motivation for science, but also provides a unique contribution to the monitoring of Denmark’s marine environment.

Registering butterflies and rare mushrooms, collecting water samples or reporting tick bites has become a widespread phenomenon for so-called citizen scientists who voluntarily contribute to various research projects. Citizen science typically involves everyday people helping to collect data or samples that are then analysed by professional researchers.

Now, researchers at the University of Copenhagen’s Natural History Museum of Denmark, in collaboration with the Danish National Union of Upper Secondary School Teachers, have gone a step further by 'promoting' students to become ‘real’ researchers.

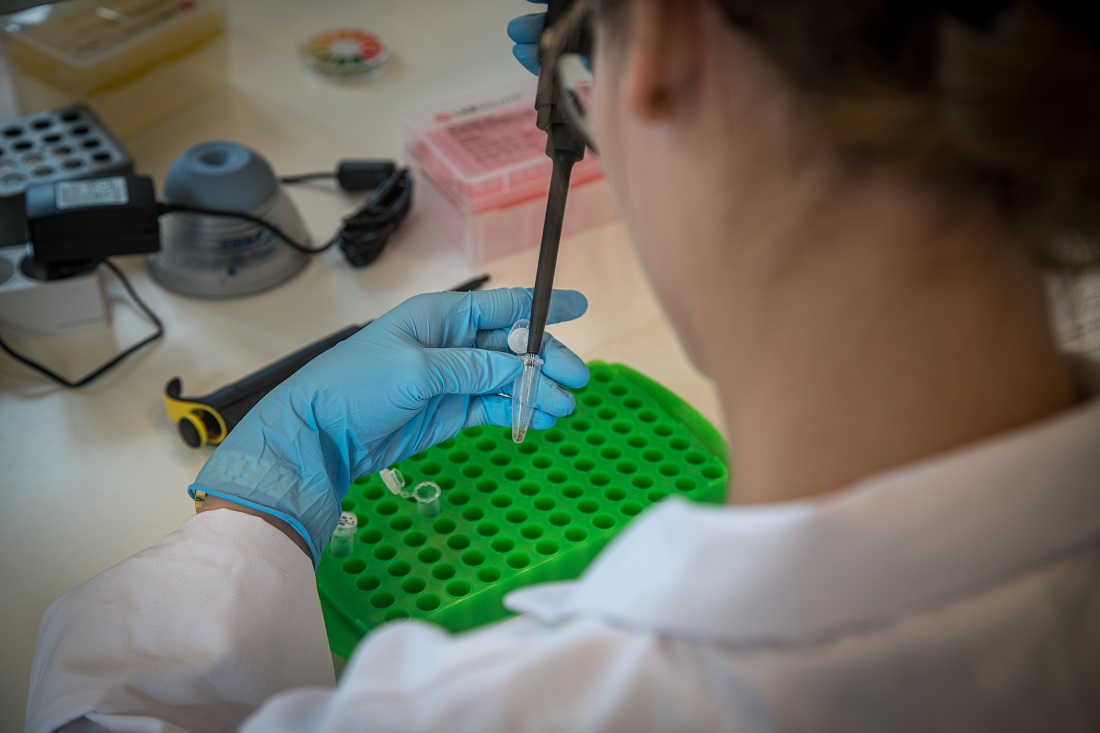

In a project that monitors Denmark’s marine environment, high school students don’t just collect DNA samples from Danish fjords, but also conduct DNA analyses in the laboratory.

Previoulsy, high school classes could visit a laboratory at the Natural History Museum in Copenhagen to conduct parts of analyses under the guidance of researchers. But now, the project has set up local laboratories at high schools in both Herning and Hjørring, Jutland where students can independently conduct lab work with their teachers. This is known as 'extreme citizen science.'

ABOUT THE PROJECT

- The citizen science project DNA & Life has run since 2017. The 'extreme' version, Extreme DNA & Life, began in 2022.

- A total of 3,300 high school students and 140 teachers have collected samples between 2017-2023. The samples cover most of the Danish coastline and fjord systems.

- Each biology teacher in the project has completed a course on using lab equipment and methods correctly. After the course, teachers can consult with researchers at the Natural History Museum of Denmark and participate in online webinars.

- The project is supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

- The research article about the project is published in the scientific journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

- The authors of the research paper are: Frederik Leerhøi, Maria Rytter, Marie Rathcke Lillemark, Jørgen Olesen, Peter Rask Møller, Nina Lundholm, and Anders P. Tøttrup from the Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen; Morten Tange Olsen from the Globe Institute, University of Copenhagen; Steen Wilhelm Knudsen from NIVA Denmark; Brian Randeris from Silkeborg High School/The Danish Biology Teachers’ Association; and Christian Rix from Rødkilde High School/The Danish Biology Teachers’ Association.

- Learn more about the project and find out how to get involved at DNApåFORKANT.dk

"Extreme citizen science is the idea that the role of a researcher becomes ever smaller. The unique and 'extreme' aspect is that a larger part of the research process, both fieldwork and lab work, is now handed over to high school students. We were excited to see if it would work and have now seen that it does so exceptionally well," says project leader Anders P. Tøttrup, Associate Professor of Citizen Science at the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

An eye-opener to a new world

The participating high school classes, who come from other Danish high schools in addition to Herning and Hjørring, have collected water samples from Limfjord and other fjords, filtered them for DNA, and conducted PCR analyses of their samples in local laboratories. The goal was to find DNA from specific species such as eel, perch, round goby, warty comb jelly and the toxic algae, Alexandrium ostenfeldii.

According to Daniel Andersen Woo Shing Hai, a biology teacher at Hjørring High School, the project offers something extra for both students and teachers:

"For many students, it's a big deal to be part of this and an eye-opener to a whole new world. Being out there collecting actual DNA samples and then coming into a real DNA lab and getting that lab feel like you see on TV shows is something that, in my experience, motivates them. I also think that it can inspire them to study biology or science after high school," says Daniel Andersen Woo Shing Hai.

He adds that there's something special to gain for teachers as well:

"It’s rewarding to work with cutting-edge developments in biology. Instead of always receiving five to ten-year-old information and then passing it on, one actually plays a part in the production of results that will be published by universities. Plus, as a teacher, it brings subject matter to life — as opposed to just running an experiment for the sake of it, it can be used in a real-world context.”

Even though high school students are the ones wearing the lab coats, there’s no compromise on research quality, emphasizes Frederik Leerhøi, one of research paper’s lead authors and an academic officer at the museum:

"We don’t cut corners on quality. On the contrary, all samples attain a standard that the scientific community accepts as valid results. This is achieved by ensuring that each student runs control tests and by subjecting our results to various algorithms to ensure for their reliability."

Great potential to improve environmental monitoring

Among other things, the scientific results of the project demonstrate that the round goby, an invasive fish species, and toxic Alexandrium ostenfeldii algae have both spread widely in Denmark. Indeed, the round goby had not previously been registered in Limfjord.

"The method seems quite effective in detecting many species — these algae for example, which we know very little about in Denmark. Even though they can cause shellfish poisoning and are potentially dangerous to both animals and humans, we barely monitor them. So, we want to raise awareness that this DNA method can be used to monitor toxic algae and many other species in our marine environment — possibly in collaboration with high schools," says Frederik Leerhøi.

The researchers are working to make use of the data and have entered an agreement with the Danish Environmental Protection Agency, which will incorporate the project's data into the national reporting to the EU on invasive species.

"We hope that this setup inspires our international colleagues to do something similar in their countries because it's plug-and-play, in that DNA analyses can be applied to any species or group of species you're interested in," says Anders P. Tøttrup.

According to the researchers, extreme citizen science can make a real difference in the monitoring of marine biodiversity:

"This has great potential to improve our monitoring and thus the conservation of our marine environment, which is generally in poor shape. We don't monitor nature very well in Denmark today as doing so is resource intense. However, projects like this can be an effective way to collect data from large parts of the country while also motivating young people to engage with and develop an interest in science," concludes Tøttrup.

The researchers hope to expand the project in such a way that DNA laboratories are established in more Danish high schools.

Contact

Anders P. Tøttrup

Associate Professor

Natural History Museum of Denmark

University of Copenhagen

aptottrup@snm.ku.dk

(+45) 51 82 69 88

Frederik Leerhøi

Academic officer

Natural History Museum of Denmark

University of Copenhagen

frederik.leerhoei@snm.ku.dk

(+45) 40 18 53 90

Maria Hornbek

Journalist

Faculty of Science

University of Copenhagen

maho@science.ku.dk

(+45) 22 95 42 83