New measurements show high air pollution in the Copenhagen metro

The concentration of harmful particles in the air is 10 to 20 times higher in the metro than on the most polluted stretch of road in Copenhagen, new measurements made by the University of Copenhagen show. More ventilation can solve the problem, according to the researchers behind the study.

Every year, air pollution is responsible for 4,200 Danes dying prematurely and is linked by the WHO to diabetes, cancer and heart disease. In Copenhagen, air pollution is measured by a number of measuring stations on rooftops around the city.

But the air underground, which is breathed by the 80 million people who use the metro each year, has been a blind spot in measuring the city's air quality. Now, researchers from the Department of Chemistry at the University of Copenhagen, in collaboration with Aarhus University, have for the first time measured the air pollution underground in the Copenhagen subway system.

The measurements show that the air is polluted with ultra-small particles harmful to health at a level that is 10 to 20 times higher than measurements taken right next to the Town Hall Square on the heavily trafficked H.C. Andersens Boulevard. A stretch which until now has been assessed as the capital's most polluted.

"Our measurements show that the metro is probably the place in Copenhagen's public space where you are exposed to the most concentrated air pollution. If you use the subway a lot or work there, it can have an impact on your health and could be the largest single item contributing to your annual exposure. Measures should be taken to reduce the concentration of particles quite a bit," says Professor Matthew S. Johnson from the Department of Chemistry, who led the study.

The air pollution in the subway comes mainly from the trains' brakes, wheels and rails, which are made of iron. The friction from the trains running and decelerating releases iron particles into the air, which make up 88 percent of the particles that the researchers were able to identify in their analyses.

The iron particles are so small that they can easily penetrate lung tissue and directly into the blood. Therefore, according to the WHO, they are, on par with other small particles, harmful to human health.

City ring and Forum are the worst

The researchers have made measurements from trains on all lines and from 14 metro stations. It is worst inside the trains themselves on Cityringen, M3, where the concentration of particles is on average 20 times higher than at H.C. Andersens Boulevard close to Rådhuspladsen and twice as high as in the trains on metro lines M1 and M2.

This is because the City ring consists of 17 underground stations and therefore gets very little ventilation down into the tunnel compared to the M1 and M2, which run above ground for some of the section.

"It is called the 'piston effect', where the trains push the polluted air out of the tunnel when they travel above ground. M1 and M2 benefit from that effect, even though the air is still increasingly polluted the further away you get from the above-ground stations. But because the City Ring only runs underground, you don't get the natural exchange in the air there, only a smaller amount of air pushed through the ventilation shafts, and therefore it is far more polluted," explains Ph.D. Hugo S. Russell from Aarhus University, who has been in charge of collecting and analyzing the samples together with Niklas Kappelt.

Forum Station take the prize as the most polluted stations across the entire metro network. It has a much higher concentration of particles compared to e.g. Nørreport, Kongens Nytorv, Christianshavn and Amagerbro.

Facts about the measurements

- In the scientific article published in the journal Environment International (Part 1) (Part 2), the researchers conclude that "the system is surprisingly polluted despite its recent construction" in 2019.

- Inside the trains on the Cityringen M3, researchers have measured that there is an average of 20 times the concentration of particles in the air as near H. C. Andersens Boulevard, which is said to be one of the most polluted places in Copenhagen.

- The Nørrebros Runddel and Forum stations are the most polluted across the entire metro network.

- The particles mainly consist of 88% iron, which originates from train rails, wheels and brakes.

- The measurements were made over 16 days in March and April 2021 and were carried out in the trains while they were running and at the stations.

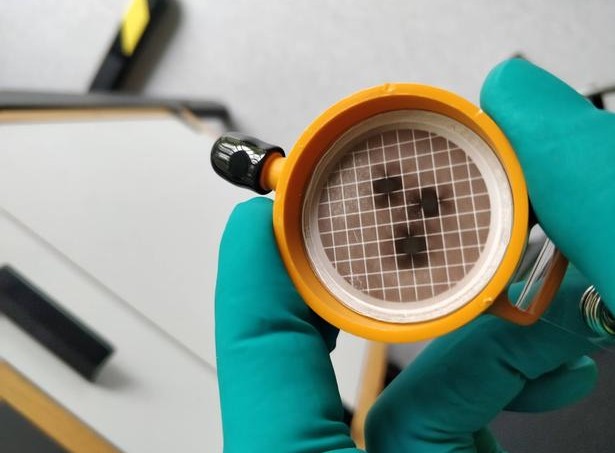

- A measuring instrument called a TSI DustTrak DRX Aerosol Monitor 8533 was used, as well as small optical particle sensors and gravimetric samplers.

- The composition of the gravimetric samples was analyzed with particle-induced X-ray emission (PIXE) analysis.

- Average levels of 109 micrograms per cubic meters was measured at underground stations on the M1 and M2 lines, this is 10 times the street level recorded in central Copenhagen at the time of measurement (11 µg m−3 ).

- For the M3 line, the average concentrations on the trains were 219 micrograms of particles per cubic metre, which is 20 times higher than street level in central Copenhagen and higher than on the platforms (168 micrograms per cubic metre), which is not typical compared to other metro systems.

- In outdoor air, the EU has a goal that the concentration of ultrafine particles over a year must remain below an average of 25 micrograms per cubic meter.

- The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that the average exposure over a year is a maximum of 5 micrograms per cubic meter, because it is estimated that more than that can potentially be harmful to health.

Ventilation can reduce pollution

According to the researchers, problems with high air pollution in metro systems are not a new phenomenon. In i.a. Similar problems have been identified in London, Paris, Stockholm, Barcelona, Seoul and Toronto, and the solution here has primarily been more ventilation of the air. The researchers estimate that this will also be able to significantly reduce the concentration of particles in the Copenhagen metro.

"In Barcelona, they simply turned on the ventilation shafts that had already been installed, but were intended for heat control, and that brought the particle concentration down. The Copenhagen subway also has a similartype of ventilation shaft intended for fires, but they are not in use today. You could consider turning them on," says Professor Matthew S. Johnson and adds:

"Otherwise you end up having to change wheels, rails and brakes to other materials. A very expensive affair but even so, something that they chose to do in the Toronto and Montreal metros,” says Matthew S. Johnson.

Another possible culprit for the pollution inside the trains is the glass doors that separate the platform from the train. They help to insulate the particles in the tunnels and reduce the ventilation there. A problem that has also been observed in South Korea.

"Studies from Seoul's subway system have shown that doors between the platform and the train track improve the air quality in the stations, but make it worse inside the trains. There is of course a safety concern, but it is worth considering," says Hugo S. Russell.

Contact

Matthew S. Johnson

Professor

Kemisk Institut

Københavns Universitet

Mobil: +45 40 49 89 21

Mail: msj@chem.ku.dk

Hugo S. Russell

Ph.D.

Institut for Miljøvidenskab

Aarhus Universitet

Mobil: +45 91 61 17 70

Mail: hugo.russell@envs.au.dk

Michael Skov Jensen

Journalist and team coordinator

The Faculty of Science

University of Copenhagen

+ 45 93 56 58 97

msj@science.ku.dk