When the face becomes a mystery: New study challenges understanding of face blindness

A new PhD thesis provides a rare insight into living with face blindness – and how research can improve diagnosis and understanding.

For most of us, it happens automatically: we recognise a face in a split second. But for people with developmental prosopagnosia – also known as face blindness – recognising people is a daily challenge.

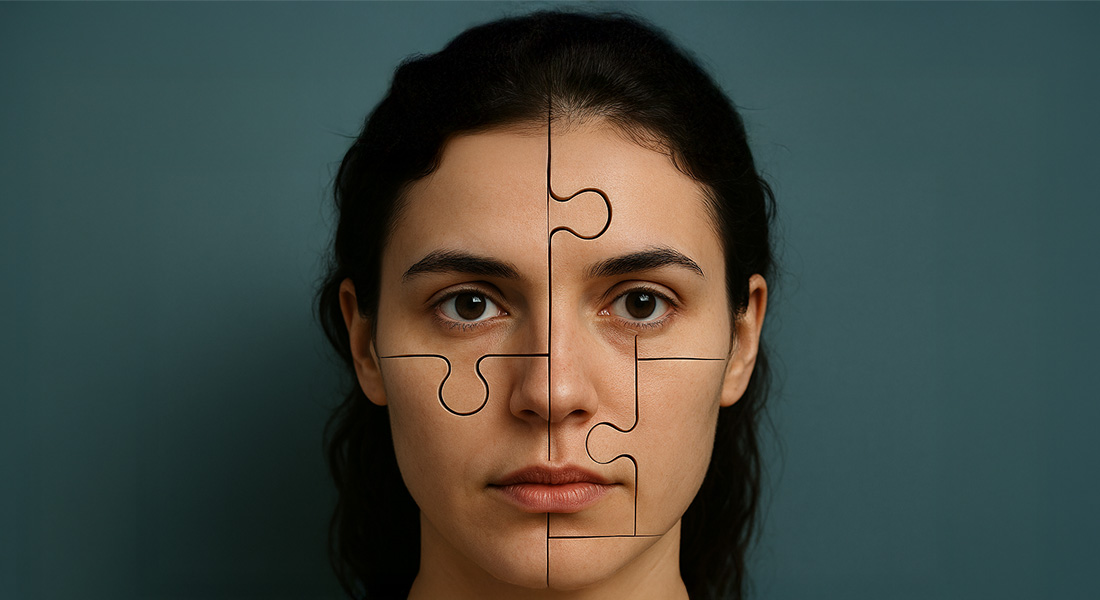

‘We know that faces are central to human interaction – from the moment we are born. But for people with prosopagnosia, the face is not a shortcut to identity. It is a puzzle that must be solved,’ says Erling Nørkær, PhD at the Department of Psychology at the University of Copenhagen.

He is the author of a new PhD thesis on face blindness – a condition that affects up to 3% of the population and causes difficulty in recognising even close relatives based on their faces alone.

When the face loses its integrity

Face blindness can occur without vision problems or brain damage – and often without the person understanding why facial recognition is so difficult. Erling Nørkær's research shows that there is a lack of consensus in the field regarding definition and diagnosis.

‘We have found large variation in how researchers classify prosopagnosia. This makes it unclear whether we are even talking about the same phenomenon across studies,’ he says.

A central part of his project is a phenomenological study of how people with prosopagnosia perceive faces. This reveals a striking pattern: faces are not seen as a whole, but as fragments.

‘Our interviews show that facial perception fluctuates between individual parts – such as the eyes or mouth – and a fleeting overall impression. What for most people is an immediate experience becomes for them a fragile construction that often falls apart,’ explains Erling Nørkær.

Recognition as problem solving

When it comes to recognising people, participants describe the process as slow and exhausting.

‘Recognition does not happen at a glance, but typically only when the other person gives a social signal – a smile or a greeting. It’s like putting together a jigsaw puzzle where the pieces are context: voice, hair, surroundings,’ explains Erling Nørkær.

In addition to the qualitative studies, the project has developed and tested new versions of the most widely used self-report questionnaire (PI20). Shorter and more precise versions can make it easier to screen for face blindness in both research and clinical settings.

‘We recommend an ultra-short questionnaire with only five questions, which can be used for rapid screening. And we point out that future tests should take into account the experiences we have uncovered – for instance, that recognition is often an active problem-solving process,’ says Erling Nørkær.

Face blindness can have major social consequences, from misunderstandings to isolation. Erling Nørkær hopes that his work can pave the way for better understanding and support.

‘If we can define what prosopagnosia is – and not just what it is not – we can develop more targeted strategies to help those who live with it,’ he concludes.

The PhD thesis is entitled ‘Beyond Face Value – The Phenomenology and Assessment of Developmental Prosopagnosia’. It can be read here.

Contact

Erling Nørkær, PhD

Department of Psychology

Email: cag@econ.ku.dk

Mobile: 23 39 20 74

Simon Knokgaard Halskov

UCPH Communication

Email: skha@adm.ku.dk

Mobile: 93 56 53 29