Thousands of intestinal viruses have now been mapped. And they can be used to fight antibiotic resistance

A new method developed at the University of Copenhagen has been used to identify more than 1,000 different types of bactericidal viruses in the human intestines. The researchers behind the new study believe the discovery may help fight antibiotic resistance.

Each year, about 700,000 people around the world die due to antibiotic resistance. According to the WHO, annual deaths could rise to 10 million by 2050, exceeding the number of people who right now die of cancer each year.

This makes antibiotic resistance one of the greatest threats to public health. Because when bacteria become resistant, otherwise harmless infections such as pneumonia can be deadly.

But perhaps the solution can be found in our own intestines.

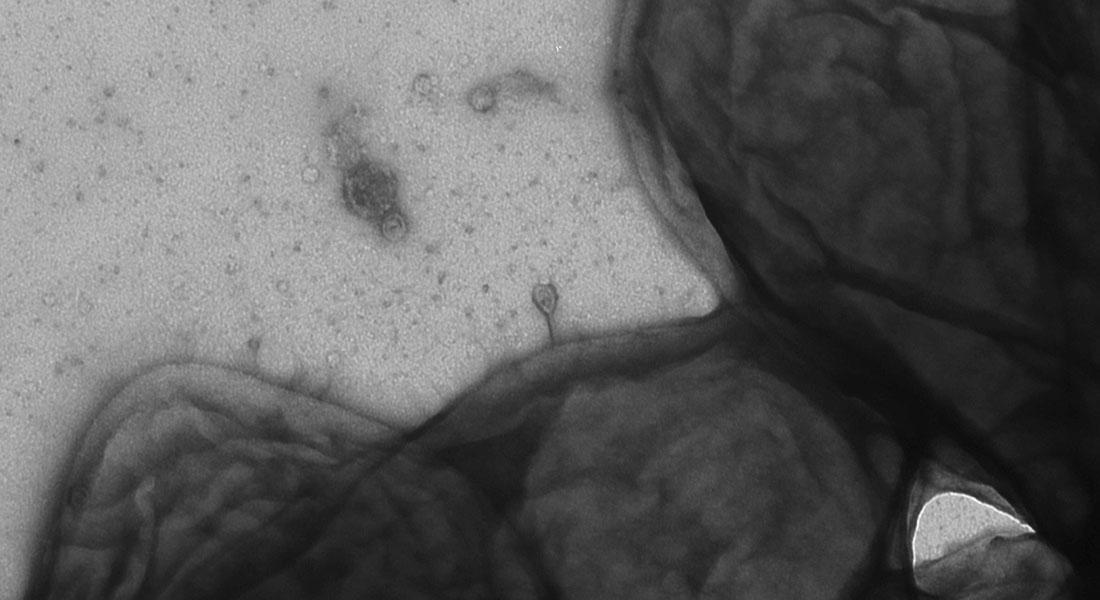

Because in our intestinal bacteria researchers from the University of Copenhagen recently identified bactericidal viruses, so-called phages, that can help fight resistant bacteria.

“Phages are by nature designed to infect bacteria, which makes them the ultimate weapon to fight dangerous bacteria that do not respond to antibiotics,” says PhD Student Joachim Johansen from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Protein Research and adds:

“The new AI-based method has enabled us to identify more than 1,000 different types of phages quickly and efficiently.”

There are other available methods for identifying phages, but they are more time-consuming as they require isolating each individual phage, whereas the method developed by Joachim Johansen and colleagues is able to identify all phages in a sample at the same time.

Phages may have fewer negative side effects than antibiotics

Aside from helping us fight antibiotic resistance, phages may turn out to have fewer negative side effects than antibiotics. Most antibiotics are broad-spectrum, which means that antibiotics such as penicillin do not merely target ‘bad’ bacteria, but also the ‘good’ ones.

Phages, though, seem to be able to target more specific bacteria.

“Phages only eliminate the one bacterium they are known to infect. This makes them extremely clever,” says Associate Professor Simon Rasmussen from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Protein Research, who has headed the study. He adds:

“The problem with antibiotics is that they can kill all microorganisms in the intestines, and this is not desirable. Because killing intestinal bacteria will change the composition.”

And a healthy balance of bacteria and phages in the intestines is paramount, because it has a great impact on other parts of the body, including our immune system, hormone production, digestion, energy level, mood and experience of pain.

“When you suffer a serious infection and receive antibiotic treatment, we know that it may impact other diseases. For example, the risk of developing mental illness increases every time you are admitted with an infection and receive antibiotic treatment. It is hard to say, though, whether it is a result of the infection or the antibiotic treatment,” says Simon Rasmussen.

He does stress that if you suffer an infection today, the best available solution is most often treatment with antibiotics.

Phages’ bactericidal qualities were discovered as early as the 1920s by French-Canadian Microbiologist Felix d’Herelle, who described them in a scientific article.

But as soon as penicillin and other antibiotics were discovered in the late 1920s, phages research was shelved. Fortunately, though, interest in bactericidal viruses has now been rekindled.

“The method we have developed is fairly easy to use. We therefore hope is will become widespread. At any rate, it holds great potential when it comes to analysing all the faeces samples collected using the new method. This way, we are able to collect lots of DNA data fast and start identifying even more phages,” says Joachim Johansen.

The full study, ”Genome binning of viral entities from bulk metagenomics data”, is available in Nature Communications.

Contact

Associate Professor Simon Rasmussen

+45 35 33 21 59

simon.rasmussen@cpr.ku.dk

PhD Student Joachim Johansen

+45 35 33 08 71

joachim.johansen@cpr.ku.dk

Press and Communications Consultant Liva Polack

+45 23 68 03 89

liva.polack@sund.ku.dk