Researchers find conclusive evidence: A large Stone Age settlement is buried in Svanemøllen Harbour

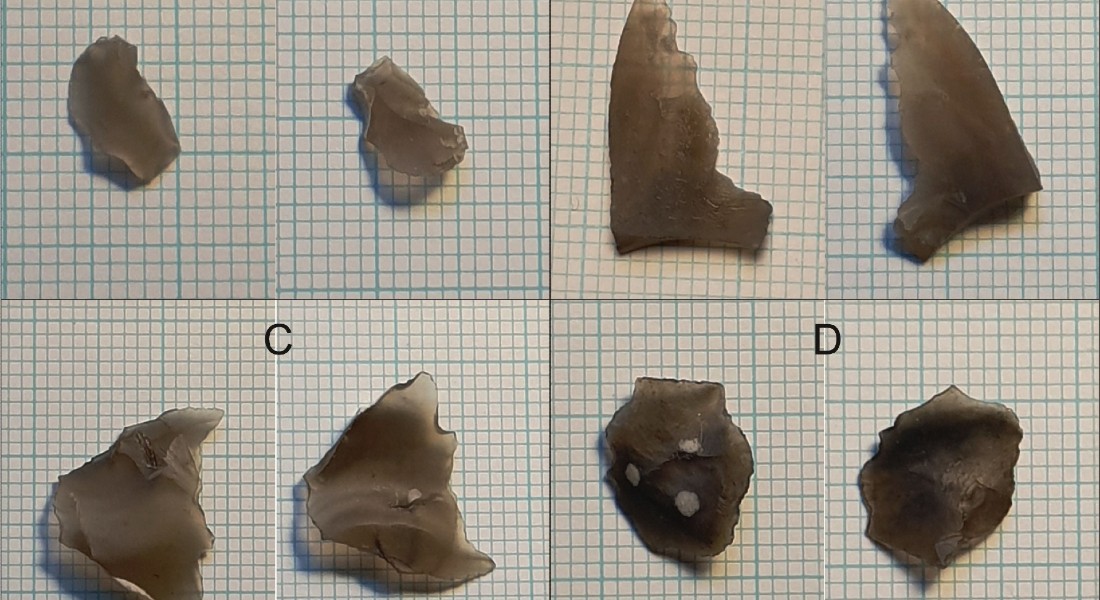

Four pieces of worked flint have been retrieved from the seabed off Copenhagen’s Svanemøllen Harbour, thus confirming the hypothesis of UCPH researchers that a many thousands of years old Stone Age settlement is hiding beneath the sea. The researchers’ find provides conclusive evidence of the settlement’s existence and that their method to locate it using acoustic signals works.

In the spring of 2021, UCPH researcher Lars Ole Boldreel and archaeologist Ole Grøn sailed out into Copenhagen’s Svanemøllen Harbour along with an apparatus to measure acoustic signals from the sea bottom. Suddenly, the device began to register powerful signals, ones that they had only heard before from worked flint stone tools at other long-submerged Stone Age sites.

However, they lacked conclusive evidence that could cement their assertion that these unique acoustics originated from the prehistoric flint tools of a buried settlement. They now have proof.

"We found four pieces of knapped flint stone, which leaves us 99.9 percent certain that there is indeed a Stone Age settlement buried just outside Svanemøllen Harbour. It's like finding a needle in a haystack, so we're really happy," says Lars Ole Boldreel, an associate professor at the Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management.

The four pieces of flint indicate a density of 500 pieces of flint per square meter, an amount consistent with the density of many other Stone Age settlements.

The worked flint is also a strong indicator of a settlement because of the stone type, which was often used for axes, arrowheads and knives by the Maglemosian people of the day. As such, the researchers consider their recovery of these four pieces as "a great victory". Their measurements also suggest that there is much more where it came from.

Acoustic signals can penetrate thick layers of sediment

The researchers used acoustic signals from the human-worked flint to survey the settlement, which they believe spans an area of 80 x 120 meters, 7–9 meters below sea level.

Two of the eight samples excavated by GEUS each delivered two pieces of flint.

"We have succeeded in proving that, by using acoustic signals from knapped flint, you could potentially locate any submerged Stone Age settlement where there is knapped flint. Not just in Denmark, but worldwide. Not to mention the fact that it's cheap and easy to do so," says Lars Ole Boldreel.

Besides the fact that the method works and has great potential to narrow our gaps in knowledge about the past, it has also set a world record.

"This is the first occasion in history that anyone has succeeded in locating a settlement at this depth beneath the sea bottom–about one meter below–using acoustic signals. Now we hope that other researchers in the field will take the method of metaphorically hearing Stone Age tools calling out from the depths, seriously," explains Ole Grøn, a visiting researcher at the University of Copenhagen.

The next step is for the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde to decide whether or not new drilling and excavation ought to be conducted in the harbour, as they are the responsible entity for archaeology on the island of Zealand. Grøn adds:

"A real archaeological excavation could allow us to find items like wooden shafts, bows, arrows and canoes. A layer of sediment has protected them from oxygen, and thereby, from rotting away in the water. Bone fragments of Stone Age people might also be discovered down there," concludes Grøn.

Different acoustic signals

- The acoustic signals registered by the researchers are not the normal echo signals known from traditional seismic surveys. Instead, it is a relatively newly discovered phenomenon called 'resonance'.

- Resonance signals mean that flint pieces affect each other's energies and resonate with each other, leading to very distinct acoustic signals.

- The method could be used to easily and effectively map underwater Stone Age settlements around the world.

Contact

Lars Ole Boldreel

Associate Professor

Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management

University of Copenhagen

lob@ign.ku.dk

+45 35322459

Ole Grøn

Archeologist and guest lecturer

Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management

University of Copenhagen

og@ign.ku.dk

+45 25101979

Ida Eriksen

Journalist

Faculty of Science

University of Copenhagen

ier@science.ku.dk

+45 93516002