MOST PEOPLE BELIEVED SHE SHOULD HAVE STAYED AT HOME. EVEN SO, SHE BECAME DENMARK’S FIRST FEMALE ACADEMIC AND GP

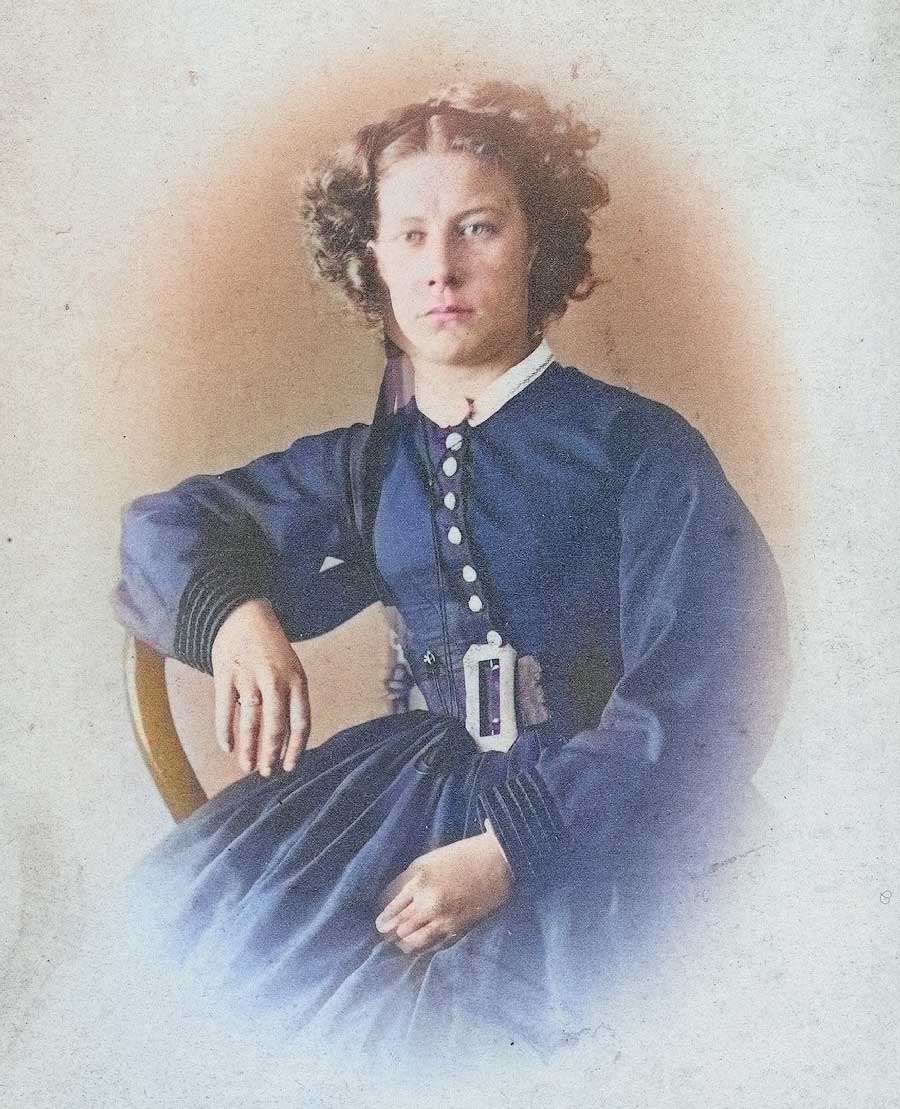

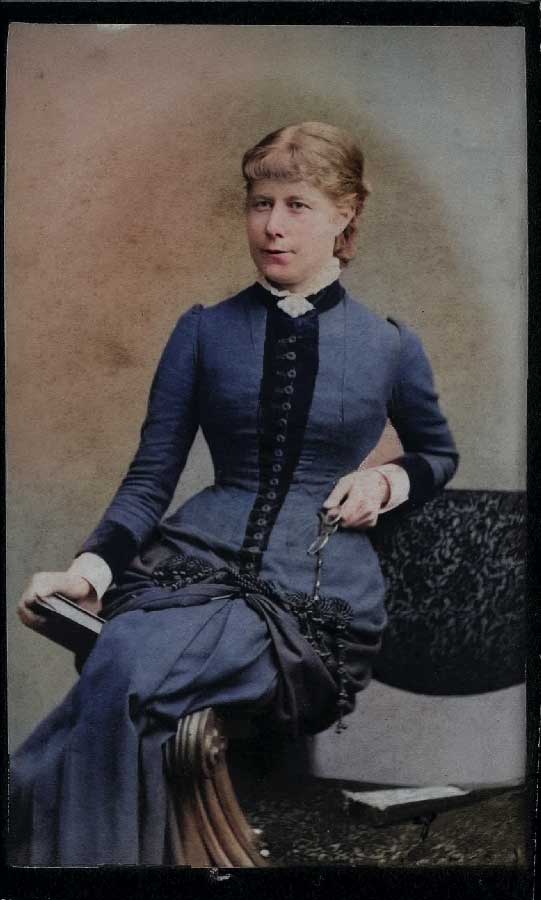

This is the story of Nielsine Nielsen. An ambitious, wistful teenager, who ended up making history by becoming the first woman in the country to get a university degree.

How we made this article

This article is based on text written by Nielsine Nielsen – in her diary as a teenager and in her memoirs as an adult. We have coloured black-and-white photos of Nielsine and her life using artificial intelligence.In 1868, young women rarely moved out of home, unless it was to get married. So it was hard to imagine that, 17 years later, Nielsine would not only have achieved her dream of moving away, but would also have become Denmark's first female GP. Yet, there were signs.

Firstly, Nielsine desperately wanted to leave her hometown, which at the time had a population of less than 5,000.

She lived with her parents. And she was the only child left in the house. Her big sister, Laura, was engaged to be married and would soon leave to live with her soon-to-be husband. Two of their siblings had already married, one had died from typhoid fever, and one had drowned in the sea.

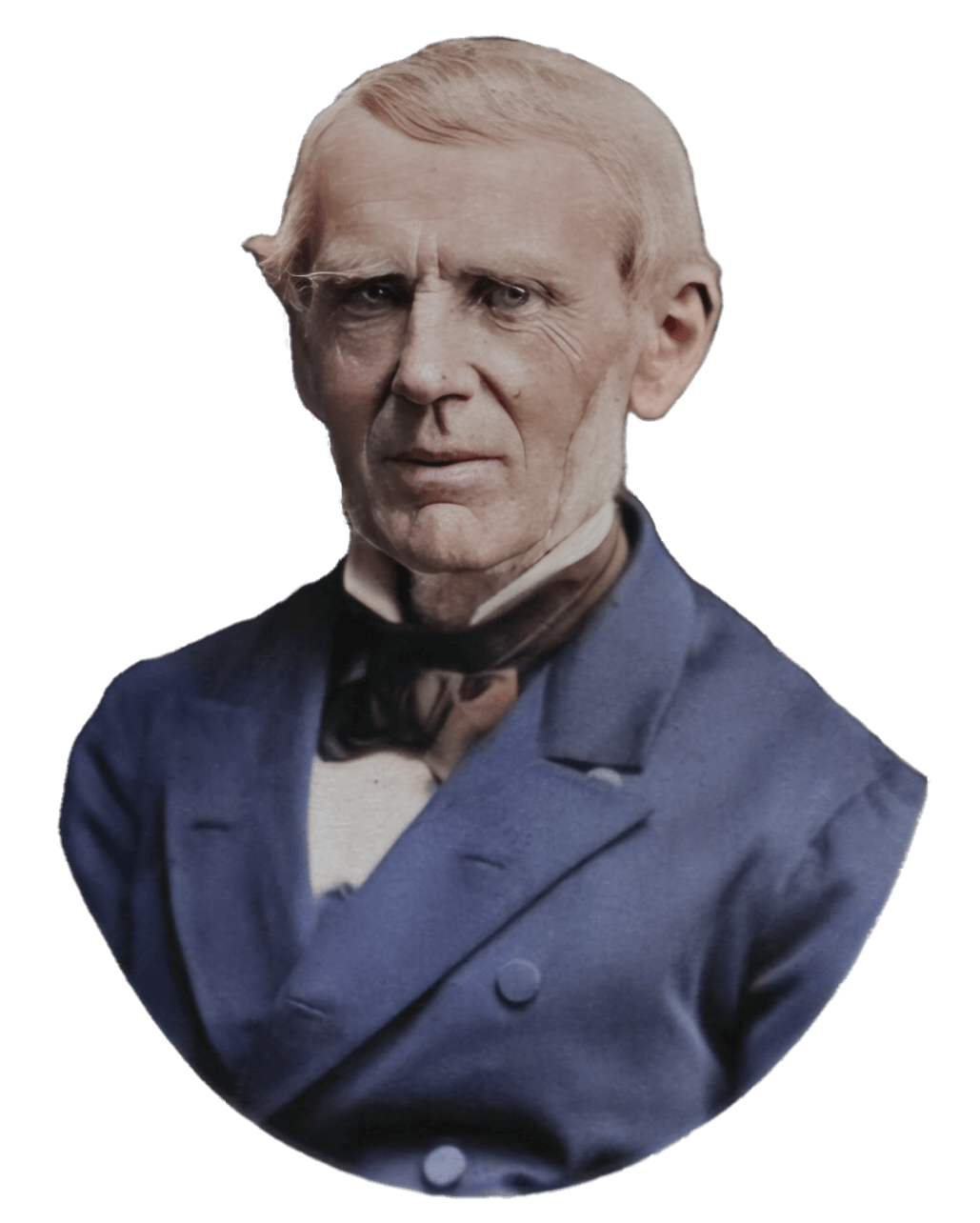

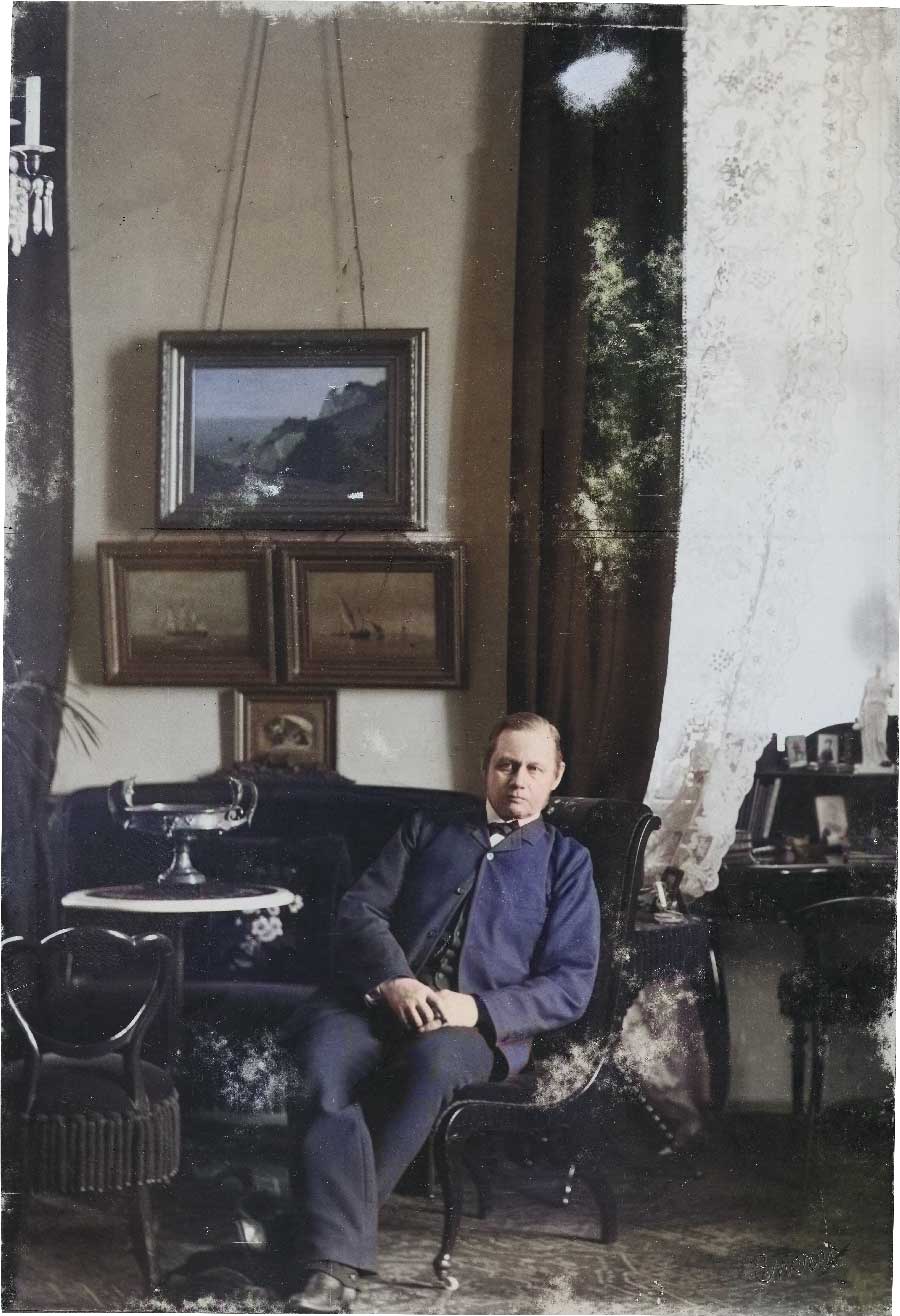

Ludvig Trier came from a wealthy upper-class family and did not have to worry about money. Instead, he invested his time in teaching young lower-class men to help them get a degree. And he felt that young women should have the same opportunities as men.

Although Nielsine spent all her spare time studying for the exam, she could not help but hear about the women’s liberation movement – the fight for women’s rights. You would think that with her ambitions, Nielsine would be a supporter of the cause.

She was not.

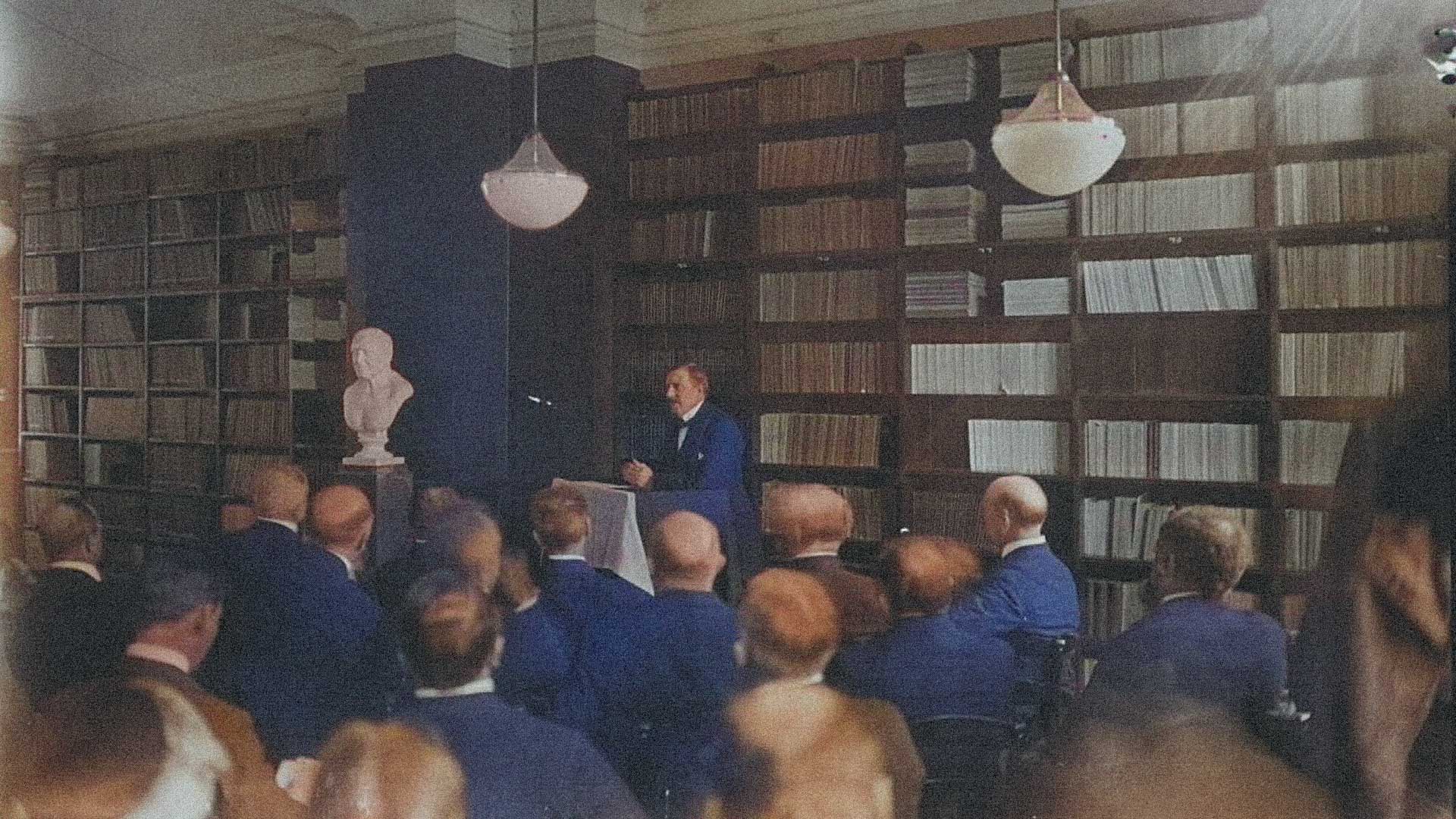

Even though she was not a fan of the ‘cause’, Nielsine accepted the offer. And after having been rejected by the headmaster and teachers at the Metropolitan School and three doctors, it must have felt good to have the support of the city’s cultural elite.

The next couple of years, Nielsine spent most of her waking hours studying. She did not remain Trier’s only female student, though. She was joined by three others who also aspired to become doctors.

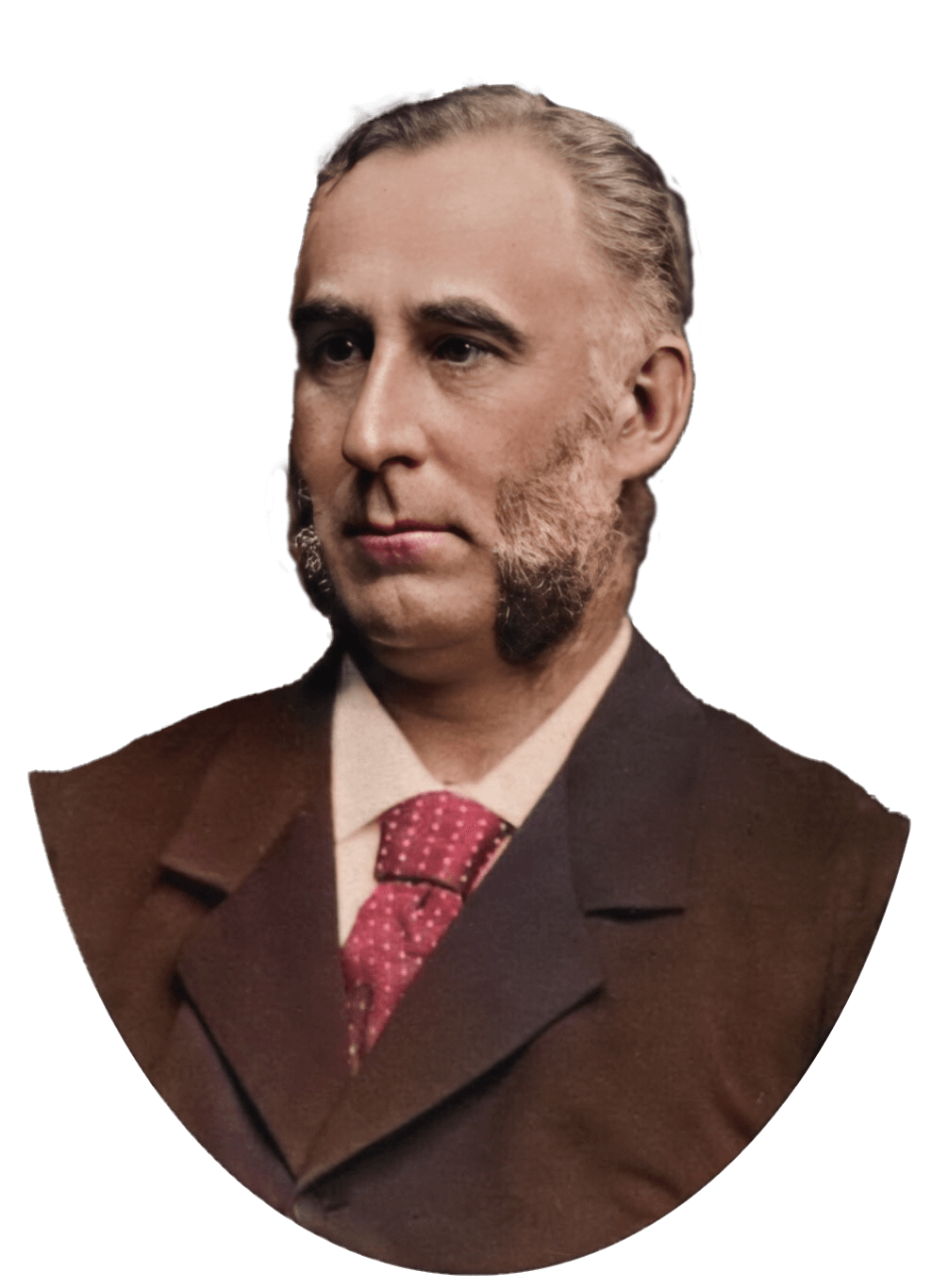

With the help of Mayor Fenger, Nielsine posted her historic application for a place at the University of Copenhagen’s school of medicine to the Ministry of Ecclesiastical Affairs and Education on 22 January 1874. If her application was approved, it would not merely give Nielsine a place at the University of Copenhagen; it would give all women in the country a chance to apply for university.

But not everyone felt that was a good idea.

And then she goes on to namedrop everyone from social debater Georg Brandes to Skagen artist P. S. Krøyer. Nielsine became a regular guest in the cultural-radical circles of the capital. It must have been quite the change from her middle-class home in Svendborg.

Even though she developed a considerable social network, she still spent most of her time studying.

Text and research:

Liva Polack

Graphics and development:

Frans Wej Petersen

Published on 8 March 2024

References

- Royal Danish Library

- "Nielsine Nielsen – Danmarks første kvindelige læge og akademiker" by Dorthe Chakravarty & Sarah Von Essen

- Læge Frk. Nielsine Nielsens erindringer (Doctor, Miss Nielsine Nielsen’s memoirs)

- Anna Cecilia Westerberg, who is related to Nielsine Nielsen, and who has shared private photos with us.