On a summer’s day in 1932, Inge Lehmann embarks on the journey of a lifetime. The 44-year-old usually spends her summer holidays sweating on Europe's steep mountain sides. But this summer, she's not going anywhere.

She is at her desk in her small, whitewashed cottage on a hilltop in Holte outside Copenhagen, surrounded by maps and cardboard boxes filled with documents. Each box contains data about arrival times and wave strengths from an earthquake at a specific location. One box with data from Tokyo, one from Vienna, one from London.

Slowly but surely, Inge Lehmann follows the earthquake waves through the many layers of Earth on a voyage of discovery into its burning inner core. 5,100 km beneath the surface of Earth, she discovers something no one else has seen before.

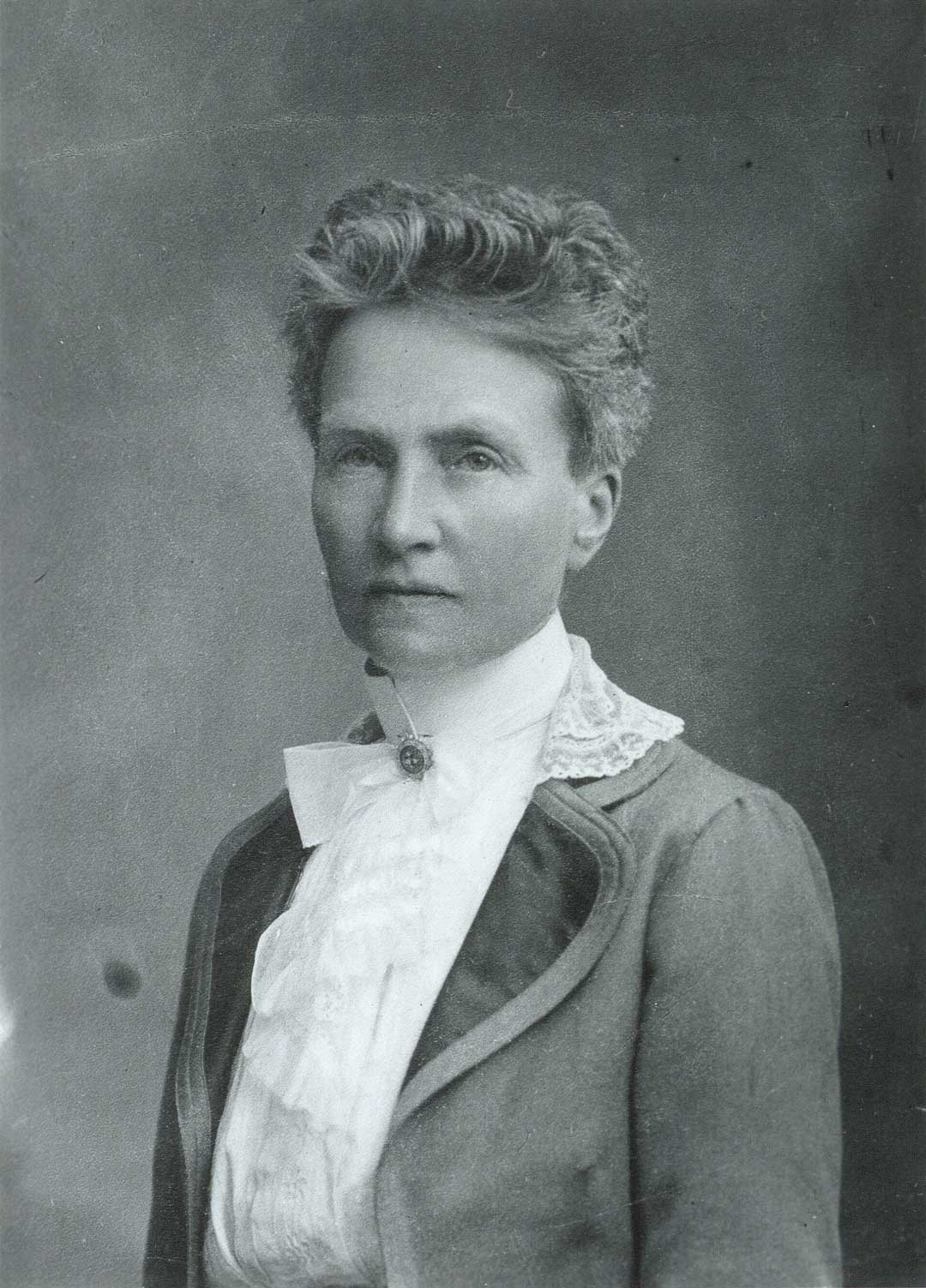

Gifted child

Inge Lehmann was born in May 1888 in a flat on Willemoesgade in Østerbro, Copenhagen. Her mother Ida was from a family of bookstore owners and members of the women's movement. Her father, Alfred, was an engineer and later founded psychology as a scholarly discipline in Denmark. Her parents believed that boys and girls should have the same education, so they sent Inge Lehmann and her younger sister, Harriet, to the progressive and liberal H. Adler Fællesskole, a co-educational institution located by Lake Sortedam in Copenhagen. Girls and boys are in the same class, and everyone learns to cook, saw wood, embroider and play football.

Inge Lehmann was happy with her school days, and many years later she wrote:

At a school prom, Ida and Alfred Lehmann find their 11-year-old daughter together with some older boys, deeply engrossed in solving quadratic equations. Inge Lehmann is an exceptionally gifted child with a particular flair for mathematics. She is ambitious, serious and shy. She strongly believes in her abilities and dreams of becoming a scientist. Maybe because her schoolteachers inspire and challenge her.

However, her parents are concerned as to whether she can cope with the pressure and her high ambitions, whereas she feels that her parents are holding her back.

The hardest and most prestigious education

At the age of 19, Inge Lehmann embarks on her mathematics studies at the University of Copenhagen, where she earns her bachelor's degree. She immensely longs to see the world and dreams of excelling. She goes to Cambridge to begin the Mathematics Tripos course, which is known as one of the most challenging and prestigious degrees in the world. The exams are so extensive and lengthy that students row, swim and run alongside their studies to enhance their stamina and intellect.

Inge Lehmann loves her new life in Cambridge, where she is making female friends for the first time. In a letter full of English expressions, she writes to her mother that it’s her:

Even though women have had access to the lectures on the course for 30 years, they still do not have access to the study facilities when Inge Lehmann arrives. Women are not permitted in the libraries or laboratories, where individual supervision and exercises take place. Inge Lehmann is ambitious, and perhaps also under financial pressure, so she plans to complete the course in one and a half years, even if the norm is three to four years. She is working overtime.

After a year of intensive studying, Inge Lehmann begins to suffer stomach pains. She has difficulty concentrating on her studies, her hair is falling out and she sleeps poorly at night. In the end, she cannot get out of bed, and she does not sit the exam.

Tired and burnt out, Inge Lehmann goes home to Denmark for Christmas, but she is determined to return to Cambridge in the new year. Meanwhile, her father is so worried about whether she can handle the pressure that he, to Inge Lehmann's enormous frustration, refuses to finance the rest of her course.

Inge Lehmann's family has supported her for a long time, but they were probably also influenced by the widespread perception at the time that women could become ill from doing difficult intellectual work. Several prominent doctors believe that young women's fertility may be jeopardised if they study too much and exert themselves too hard.

No one knows precisely why Inge Lehmann was taken ill at Cambridge. Many of the first female academics experience similar breakdowns early in their careers. Perhaps because they are trying to overcompensate academically to show that they are just as capable as their male peers.

Inge Lehmann loves her new life in Cambridge, where she is making female friends for the first time. In a letter full of English expressions, she writes to her mother that it’s her:

Even though women have had access to the lectures on the course for 30 years, they still do not have access to the study facilities when Inge Lehmann arrives. Women are not permitted in the libraries or laboratories, where individual supervision and exercises take place. Inge Lehmann is ambitious, and perhaps also under financial pressure, so she plans to complete the course in one and a half years, even if the norm is three to four years. She is working overtime.

After a year of intensive studying, Inge Lehmann begins to suffer stomach pains. She has difficulty concentrating on her studies, her hair is falling out and she sleeps poorly at night. In the end, she cannot get out of bed, and she does not sit the exam.

Tired and burnt out, Inge Lehmann goes home to Denmark for Christmas, but she is determined to return to Cambridge in the new year. Meanwhile, her father is so worried about whether she can handle the pressure that he, to Inge Lehmann's enormous frustration, refuses to finance the rest of her course.

Inge Lehmann's family has supported her for a long time, but they were probably also influenced by the widespread perception at the time that women could become ill from doing difficult intellectual work. Several prominent doctors believe that young women's fertility may be jeopardised if they study too much and exert themselves too hard.

No one knows precisely why Inge Lehmann was taken ill at Cambridge. Many of the first female academics experience similar breakdowns early in their careers. Perhaps because they are trying to overcompensate academically to show that they are just as capable as their male peers.

New opportunities

It will be no less than seven years before Inge Lehmann sets foot at a university again. She has spent the years calculating endless policies at an insurance company and has since moved out of her parents' home. But her job is tedious:

When a long-time friend asks her to marry him around the same time, she accepts his proposal. She has, however, always been lukewarm about the idea of marrying him, and she has a quick change of heart. Without a job and husband, but full of renewed energy, 30-year-old Inge Lehmann decides to once again delve into geometry, trigonometry and differential calculus at university. Two years later, in 1920, she graduated with a degree in mathematics from the University of Copenhagen.

When a long-time friend asks her to marry him around the same time, she accepts his proposal. She has, however, always been lukewarm about the idea of marrying him, and she has a quick change of heart. Without a job and husband, but full of renewed energy, 30-year-old Inge Lehmann decides to once again delve into geometry, trigonometry and differential calculus at university. Two years later, in 1920, she graduated with a degree in mathematics from the University of Copenhagen.

Working as a secretary or research assistant is often the end position for many of the first female scientists. But Inge Lehmann tells Niels Erik Nørlund that she dreams of working in research. He is busy setting up seismographic stations in Denmark and Greenland, and a couple of years later, he hires 37-year-old Inge Lehmann as his assistant. It’s not mathematical work, but seismology relies heavily on mathematics, so she still benefits from her mathematical skills.

First glance

One day, Niels Erik Nørlund and a small group of men, full of expectation, go down to the basement to look at some large, newly arrived instruments they have ordered from abroad. Inge Lehmann is not invited, but she tags along anyway. After a while, the men give up trying to figure out how the instruments work and go back up. Inge Lehmann is curious about the instruments that reputedly can look into Earth's interior, so she stays in the basement and examines them more closely.

The seismograph, as it’s called, consists of a heavy mass suspended from a spring. When Earth shakes, the suspended mass remains still while the frame around it moves. The movements are transferred to a piece of bromide paper – a seismogram. The stronger the quake, the greater the moves on the seismogram. Because it is known how quickly the waves travel through the Earth, seismologists can calculate the strength and location of an earthquake by comparing arrival time and wave strength at several locations.

Inge Lehmann's talent is obvious to Niels Erik Nørlund, and he sends her on a study trip around Europe, where she is given a crash course in seismology from some of the world's leading seismologists. Back home, she sits the exam and obtains an extended master’s degree in geodesy – a newly established discipline on the shape and size of Earth and celestial bodies.

Niels Erik Nørlund appoints Inge Lehmann head of the seismic department at the newly established Geodetic Institute, where she oversees operations at the seismic measurement stations in Denmark and Greenland.

Inge Lehmann is delighted with her new job and writes to Niels Erik Nørlund:

However, slowly, it dawns on her that her colleagues are not so keen on having a woman as their boss:

Research is not part of Inge Lehmann's job, so she spends her evenings, weekends and holidays working with seismic measurements.

She doesn't know it yet, but she is stumbling close to making the discovery of her life and adding one of the last pieces of the puzzle of understanding Earth's interior.

Shakes near Copenhagen

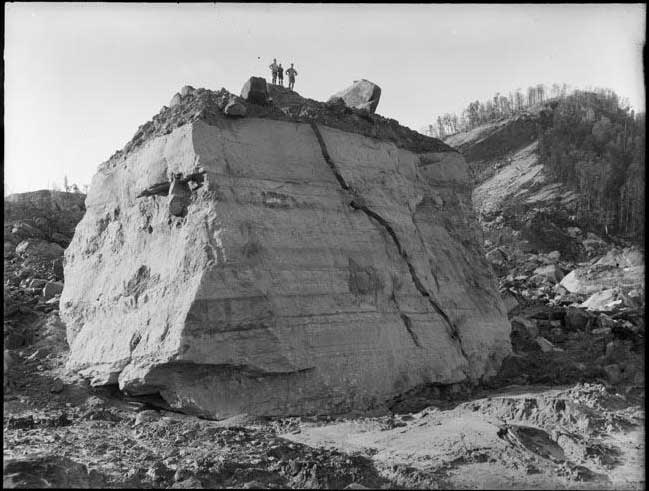

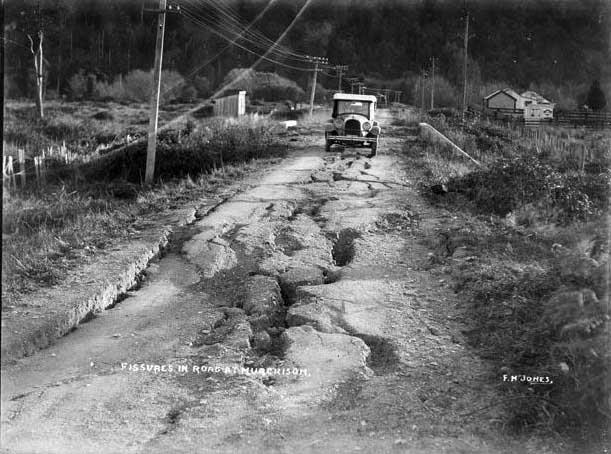

It’s a little past ten in the morning on 17 June 1929 when the ground begins to move in a sparsely populated mountainous area on New Zealand's South Island. Several square kilometres of land rise five metres into the air. Deep cracks form in the mountains, a river twists, roads are blocked by large stones and houses collapse. Beneath the New Zealand surface, the shakes spread rapidly like waves through stone, iron and nickel. Fifteen minutes later, a seismograph in Rødovre, Denmark, on the other side of Earth begins to move.

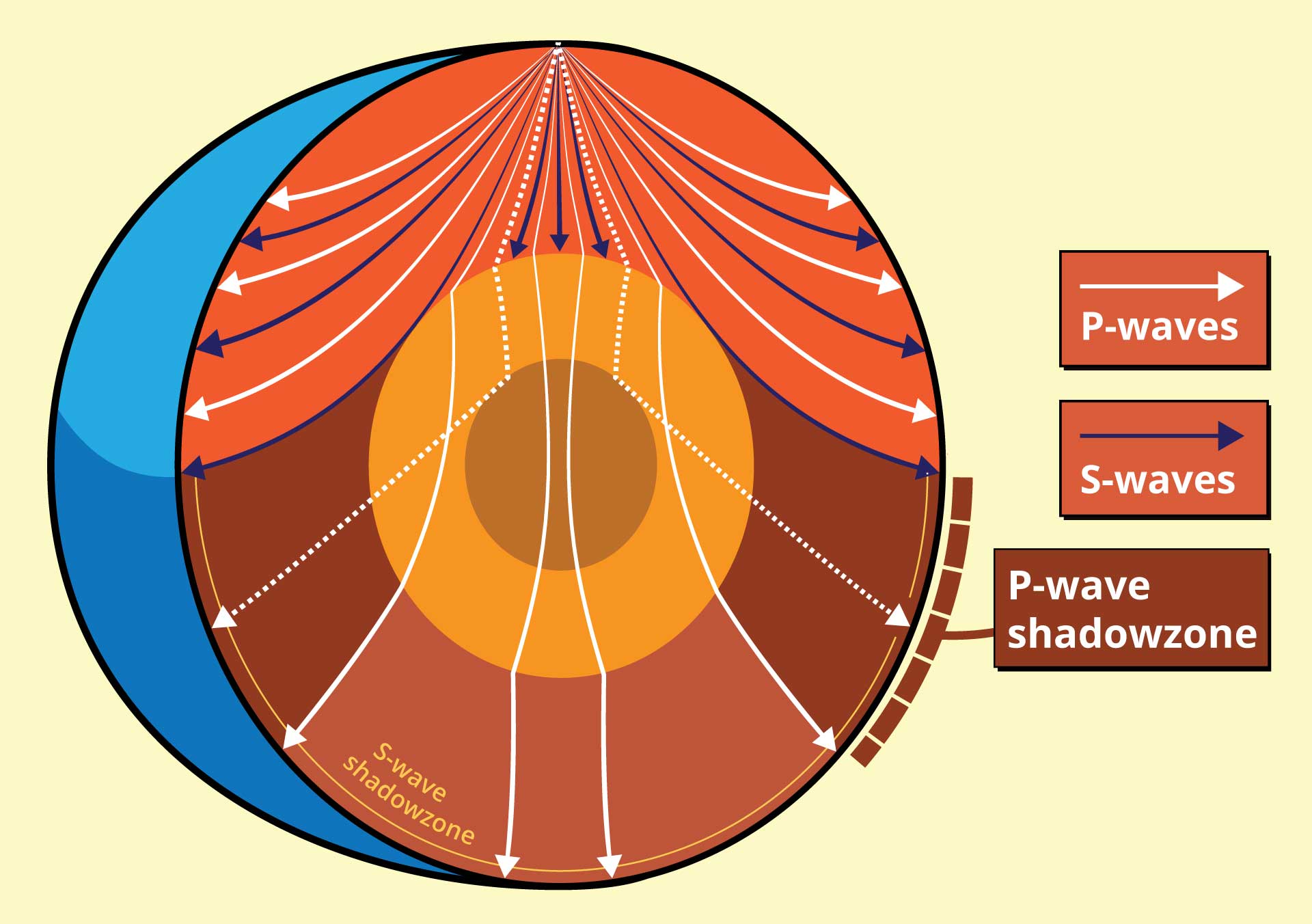

An earthquake triggers different types of waves, including P-waves and S-waves. The fast P-waves make their way through Earth like pressure waves through a spring, and the slightly slower S-waves make Earth move like a skipping rope..

If an earthquake hit the North Pole, the S-waves would be seen on seismographs across the entire Northern Hemisphere but would stop around the Equator. In 1926, this led seismologists to conclude that Earth must have a liquid inner core. As they cannot travel through liquids, the S-waves that hit the liquid core do not get to the other side of the core. In contrast, the P-waves can travel through liquids, but when they hit the liquid core, they change direction like light waves hitting a mirror. On both sides of Earth, there are areas where the P-waves never arrive – so-called shadow zones.

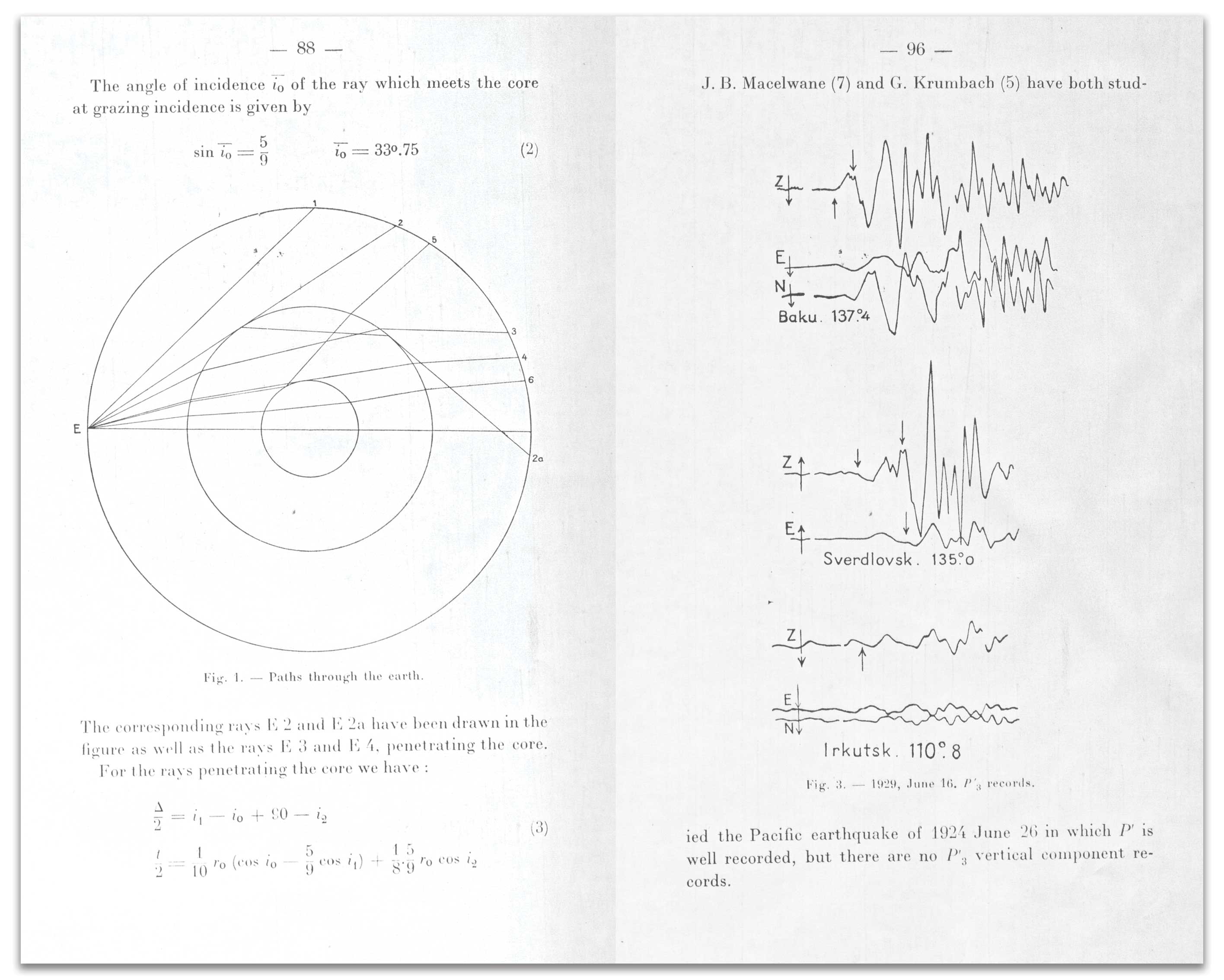

After the earthquake in New Zealand, Inge Lehmann discovers something curious: Several seismographs in Europe have registered a few P-waves from the quake, even though they are in the shadow zone. She closely studies multiple seismograms from different locations to map the path of P-waves through Earth's interior. And then she has an idea: When the P-waves from the earthquake travel through Earth's liquid core, some of them hit another core. A hard core that deflects the waves and sends them to the shadow zone, where they otherwise should not arrive.

Graphics: Frans Wej Petersen

Inge Lehmann has done her groundwork and is confident that her calculations are correct. She writes to her good friend and colleague in England, Harold Jeffreys, who, a few years earlier, discovered Earth's liquid core. She criticises his work and that of Beno Gutenberg and Charles Francis Richter (who developed the Richter scale, which is still used to measure the strength of earthquakes) for not being thorough and patient enough:

Inge Lehmann is not the only one who is puzzled by the P-waves in the shadow zone, but unlike the others, she is convinced that it’s not just due to errors in the seismographs she helped install. She insists on reading the seismograms herself, and she knows how to tell tiny blobs from wave oscillations on the black paper strips. Inge Lehmann's brain is like a human computer, phenomenal at organising data, crunching numbers, and finding connections between small, displaced seismic events and refracted waves.

She has made a groundbreaking discovery that enhances our understanding of the Earth's interior. But her life goes on as if nothing had happened. It will be 16 years before Inge Lehmann's life takes a new direction.

American recognition

On a spring morning in 1952, 64-year-old Inge Lehmann takes a couple of heavy suitcases onboard and settles into the American military aircraft that has come to take her across the Atlantic. She spends the next three months at the Lamont Geological Observatory at Columbia University, where, along with American geophysicist Maurice Ewing and a small team of the world's leading earthquake experts, she works to develop a kind of seismic espionage.

Inge Lehmann has been headhunted by the Americans, who need the Danish earthquake expert to help detect secret nuclear explosions. Like earthquakes, nuclear test explosions send shakes through the Earth's interior that can be registered on seismograms. By comparing data from multiple locations, it’s possible to determine the location and strength of the explosion. Suddenly, seismology has gained significant political attention.

Inge Lehmann retires from the Geodetic Institute in Denmark to focus on her American research adventure:

Inge Lehmann has been headhunted by the Americans, who need the Danish earthquake expert to help detect secret nuclear explosions. Like earthquakes, nuclear test explosions send shakes through the Earth's interior that can be registered on seismograms. By comparing data from multiple locations, it’s possible to determine the location and strength of the explosion. Suddenly, seismology has gained significant political attention.

Inge Lehmann retires from the Geodetic Institute in Denmark to focus on her American research adventure:

Inge Lehmann certainly does not waste time in the next 20 years, her most active research period. She crosses the Atlantic many times and spends long periods doing research at Columbia University, the University of California and Berkeley University, among others.

She especially feels at home at the Lamont Geological Observatory just north of New York City, where she resides in a small guesthouse during her stays. Every morning, she puts on her hiking boots and goes walking in the surrounding forests before the day's work. During one of her stays, she paints the kitchen in the guesthouse because it looks a bit worn.

It’s probably the first time in Inge Lehmann's life that she truly feels free and recognised for her work. The quiet and shy woman has finally become part of an academic community and formed close friendships, something that was missing from her previous life.

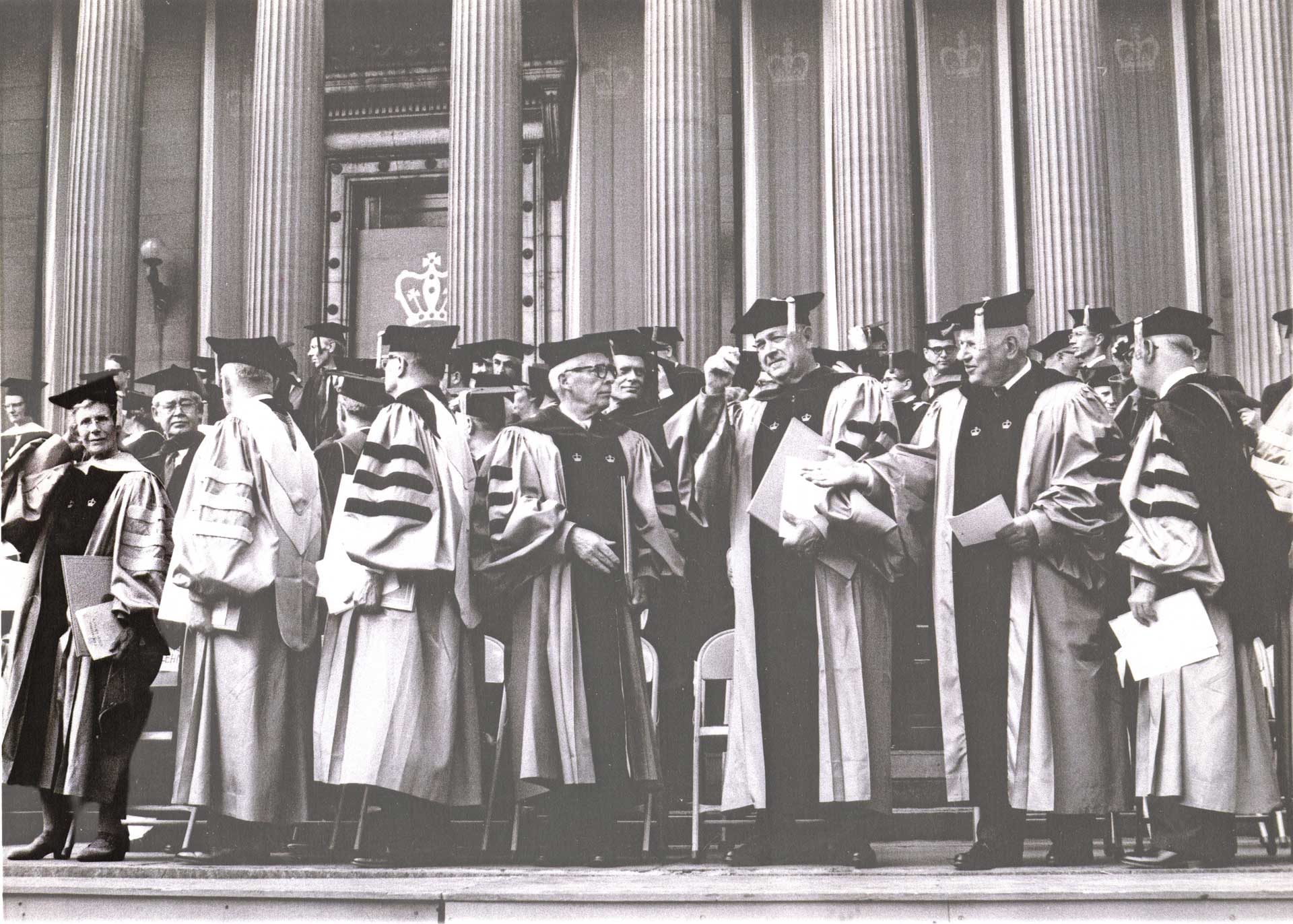

World fame 25 years delayed

In 1961, computers calculated that Earth's inner core is solid and has a radius of 1,200 km. Inge Lehmann's 25-year-old theory was confirmed, and the news about the woman who discovered Earth's inner core quickly spread around the world. In the ensuing years, Inge Lehmann gets the credit she is due. She receives a host of awards and prizes for her work, including the Bowie Medal, the highest award in geophysics in the US. Columbia University and the University of Copenhagen also award her an honorary doctorate.

Inge Lehmann is honoured for her unique ability to see even the tiniest wave oscillations and spot seismic correlations in large data volumes. In her early 80s, her vision begins to fail her. After two decades of glory, she finally retires.

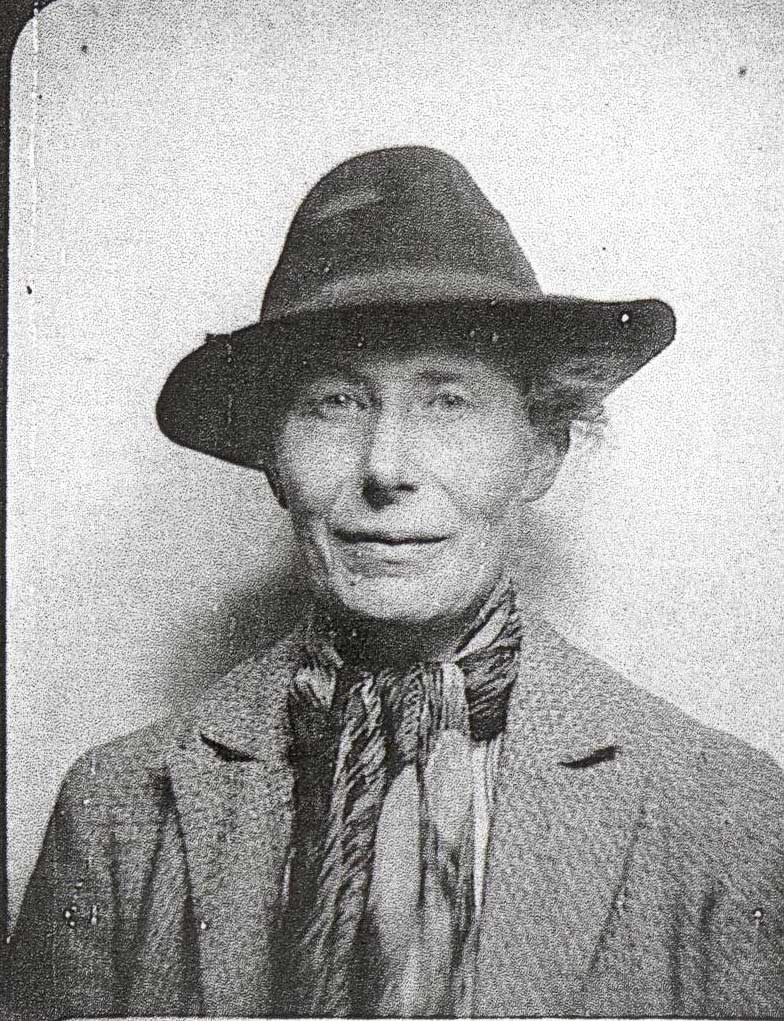

Inge Lehmann arrived at her centenary celebration in high spirits and a colourful shirt. Her vision is weakened, and she has to lean on a stick, but she can still deliver a couple of quick remarks to her former colleagues.

Friends and colleagues from around the world have come to celebrate her long life. The speeches are recorded, and Inge Lehmann often sits in her flat in Copenhagen, listening to the speeches that cherish her remarkable life and research career.

After 104 years, Inge Lehmann is ready for the final full stop. From a hospital bed, she tells her nephew:

She died on 21 February 1993 and is buried in Hørsholm Cemetery in a modest grave next to her father.

Inge Lehmann dedicated her life to research and fundamentally changed our perception of the Earth's interior. Many theories had attempted to explain what lies beneath the surface of Earth: A hard stone ball, a cavity with a glowing core or a globe that slowly shrinks and forms mountain ranges on the surface. Inge Lehmann put an end to the speculation with her groundbreaking discovery of the inner solid core. She was persistent, thorough and insisted on doing things her way – and she knew she was right.

Graphics and code: Frans Wej Petersen

Translation: Hanne von Wowern

Sources:

Interview with Lif Lund Jacobsen (Arctic Institute) and Trine Dahl-Jensen (GEUS)

- Skyggezone: A biography of Inge Lehmann, the woman who discovered Earth's inner core by Hanne Strager

- Inge Lehmann – seismologiens pionér by Lif Lund Jacobsen

- Seismology in the Days of Old by Inge Lehmann

- Memorial Essay: Inge Lehmann (1888-1993) by Bruce A. Bolt and Erik Hjortenberg

- Kongerigets glemte Inge by Gunver Lystbæk Vestergård and Lif Lund Jacobsen

- Inge Lehmann – Studietid og tidlige akademiske ansættelser 1907-1928 by Lif Lund Jacobsen

- Intellectually gifted but inherently fragile – society’s view of female scientists as experienced by seismologist Inge Lehmann up to 1930 by Lif Lund Jacobsen